Dom Cooper summarises his recent EHS Congress session, where he dissected Safety Differently and behavioural safety.

When trying to improve company safety cultures, our social, behavioural and situational expectations become the inputs to a change or transformation process, whereby the company’s leadership determine appropriate strategic safety improvement goals, expect everyone to commit to delivery of the strategy, and determine the entity’s managerial practices to ensure the strategy and goals are achieved. The ‘tangible’ outputs can usually be seen in the amount of effort or otherwise that all company personnel display on a daily basis to try to ensure the prevention of harm2.

In 1989 the British HSE3, making use of James Reason’s ‘Swiss Cheese’ model4, showed that ‘senior leadership, line-management and non-operational support functions such as HR’ directly caused around 70 percent of all workplace incidents, by, for example, introducing system faults3. With workarounds taking place to overcome the attendant problems, the associated behaviour(s) become the trigger that aligns various system faults into incident trajectories, which are either stopped from causing harm by effective risk controls, or any ineffective defences are breached and incidents occur. This can be a personal injury (e.g. Serious Injury or Fatality) or a catastrophic industrial disaster (e.g. Macondo). In either event, this and later research, shows the competency and commitment of company leadership to controlling safety issues is the key to a company’s actual OSH performance.

In response to perceived OSH problems, new ways of thinking about OSH evolve and are adopted by some. One example is the 2012 inclusion of the specific targeting of Serious Injuries and Fatalities (SIFs) into behavioural safety processes in the USA, based on research examining Heinrich’s Triangle5. Another approach, and one of the most vocal, is Safety Differently founded in 2012 by John Green, Sidney Dekker and others in Australia, which eschews traditional OSH approaches. Safety Differently is marketed as “A movement within the safety industry that challenges organizations to view three key areas of their business differently – how safety is defined, the role of people, and the focus of the business.” The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines a “Movement” as “A group of people working together to advance their shared political, social, or artistic ideas”. However, after a decade of practice, the effectiveness of Safety Differently for impacting OSH performance is now being called into question.

Widespread OSH approaches such as Behavioural Safety that target specific work-related behaviours to prevent them becoming the trigger for a harmful incident, that themselves were relatively new in the 1980s and 1990s, are often denigrated and called into question by Safety Differently advocates and others for various reasons. Behavioural Safety is defined as “A process that creates a safety partnership between management and employees that continually focuses people’s attentions and actions on theirs, and others, daily safety behaviour.” The OED defines “Process” as “A series of actions or steps taken in order to achieve a particular end (i.e. a goal)”.

When comparing the underlying rationales of the two approaches to OSH it appears the real difference is between the espoused ideology of a ‘movement’ and the pragmatic ‘processes’ of behavioural safety to improve work-related behaviour and reduce injuries. This can be readily seen when contrasting the challenges Safety Differently invite the OSH profession to consider, against the practicalities of basic behavioural-safety processes.

Challenge 2, sees Safety Differently asserting that “People are the solution, not the problem to control” and that the OSH profession need to Trust & Empower the workforce. Behavioural Safety has always relied upon people to provide appropriate solutions with Trust & Empowerment being at the centre of any successful Behavioural Safety process.

Challenge 3, sees Safety Differently assert the focus of the business should be less on telling people what to do and reducing bureaucracy. They suggest devolving responsibility, decluttering existing procedures, and decentralising power and authority. Behavioural Safety postulates that work groups identify any key concerns influencing peoples specific OSH behaviours and deal with them. In other words, “Devolve to Resolve issues (related to equipment/systems/procedures, etc.).

The brief summary above, reveals that behavioural safety incorporated the challenges of safety differently as part of its development in the 1970s, and does not consider them ‘new’ or ‘different’. A description of a basic behavioural-safety process makes this apparent.

- Identifying a limited set of workplace safety-related behaviours to place on a checklist: Ensuring the behaviours are known to be associated with injuries gives people some degree of measurement precision and operational control.

- All company personnel conducting regular observations & having safety conversations: Reinforces behavioural norms and psychological safety simultaneously

- Enter Observation & Conversation data into dedicated software (e.g., PEER): Computes a Percent Safe Score (i.e. the ratio of positive to negative behaviours, to provide weekly feedback to workgroups to facilitate adjustments in performance, and identifies issues they can help resolve.

- Follow-up with Corrective and/or Preventative Actions: Optimise the situation, to optimise behaviour. Reinforces situational norms.

- Hold Monthly Managerial Feedback Sessions: Keeps Executive Management informed of progress and involved.

- Celebrate successes: Reinforce successes to breed further successes.

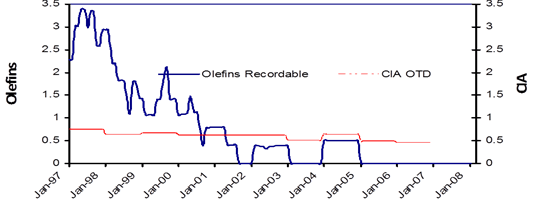

There is a large body of research that shows Behavioural Safety exerts a consistent and positive impact on improving safe behaviour and reducing injuries6. One of many, a 10 year graphical example is shown of the high-hazard Wilton Olefins 6 plant, (facilitated by Paul Rayson the coordinator and strongly supported by leadership, the lads and contractors), which simultaneously focused on process safety and personal injury related behaviours.

Figure 1: Olefins 6 example of injury reductions arising from their Behavioural Safety Process

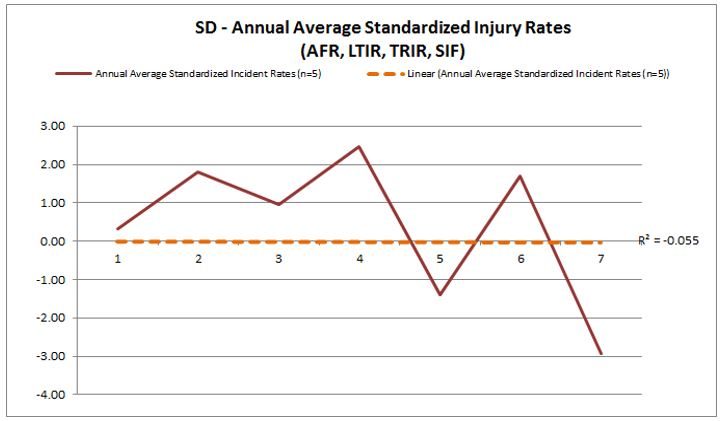

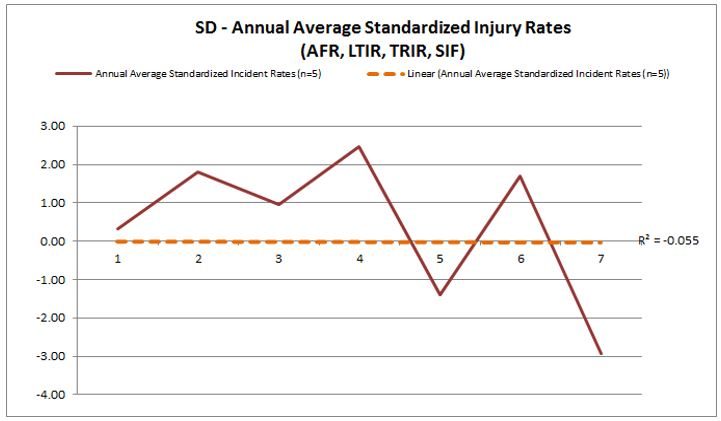

Discovering the impact of Safety Differently is not quite so simple, as they do not provide any practical information about their approach. Fortunately, corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports provide statistics of OSH performance. The CSR reports of companies (Construction, Oil & Gas, Shipping) known to have adopted Safety Differently were examined. The Injury statistics (AFR, LTIR, TRIR, & SIFs) over a seven year period were standardised to facilitate like for like computation. The Safety Differently graphic (equivalent to a Statistical Process Control Chart) shows that from 2014 – 2020, no statistically significant impact on workplace injuries took place. Rather, the mean trend line shows a performance ‘plateau’, indicating Safety Differently does not make a difference.

The contrast in injury reductions between Safety Differently and Behavioural Safety provides an important lessons-learned for the OSH profession: Ideology on its own is not sufficient to prevent harm. OSH requires structured and consistent approaches to be successful. This has serious implications for all areas of OSH, particularly workplace stress, health & well-being, and mental health.

Dom was speaking on this subject at the recent EHS Congress in Berlin. Click here for more from EHS Congress on SHP.

- Cooper, M. D. (2016). Navigating the safety culture construct: A review of the evidence. B-Safe Management Solutions Inc.: Franklin, IN, USA.

- Cooper, D. (2002). Surfacing your safety culture. The Human Factor in the Safety Practice of the Process Industry: Empowerment of the Human Safety Resource by Involvement.

- Health and Safety Executive, (1989). Human Factors In Industrial Safety, HS(G)48. ISBN 0 11 885486 0.

- Reason, J. (2016). Organizational accidents revisited. CRC Press.

- Wachter, J. K., & Ferguson, L. H. (2013). Fatality prevention: Findings from the 2012 forum. Professional Safety, 58(07), 41-49.

- Cooper, M. D. (2009). Behavioural safety interventions: a review of process design factors. Professional Safety, 54(02).